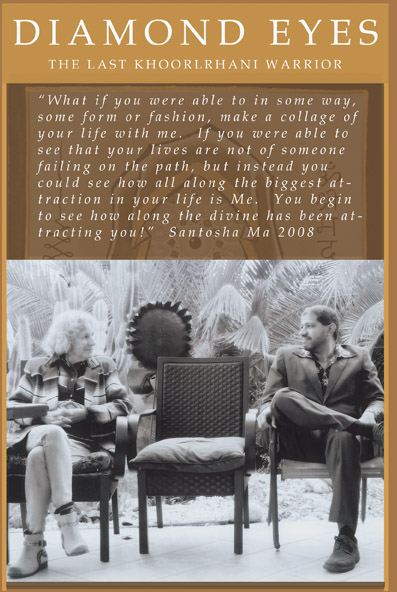

Dharmic Sci-Fi Fantasy: The Last Khoorlrhani Warrior – Chapter 9

Dharmic Sci-Fi Fantasy: The Last Khoorlrhani Warrior

The Last Khoorlrhani Warrior, is the second in the series of novels written for the Diamond Eyes series. It centers on the next generation of Khoorhani, whom Paen of Eastern Genia serves in his role as the Master. I’ve posted the first nine chapters out of about thirty three. Use the menu below to read the first nine chapters, or scroll to the bottom to download a copy. Enjoy

The Last Khoorlrhani Warrior, is the second in the series of novels written for the Diamond Eyes series. It centers on the next generation of Khoorhani, whom Paen of Eastern Genia serves in his role as the Master. I’ve posted the first nine chapters out of about thirty three. Use the menu below to read the first nine chapters, or scroll to the bottom to download a copy. Enjoy

Chapter 9: The True Reflection

The months to follow were difficult, and in retrospect I found that I still resented how the play of life moved me forward, ousting me from my comfort zones and toward accepting my place among men, unprotected and now responsible for my own life. I began to accept it though, and eventually to forget my loss. I apologized to Master Paen. I spent days picking flowers for him and brought them to him each day until he invited me in his dihj.

“Do you remember what I told you that day by the mountain years back?” I lowered my eyes. He raised my chin again and said, “Tell me.”

“You said I will chase after more loves and defend against losing the ones I have.”

“And now, do you see how that is true, that you are doing that?”

“Yes.”

“You see, Jeshibian, the supreme warrior sees this tendency in himself all the time and avoids this mistake because he knows that he is actually no one, only a reflection of eternity. You forgot something else I told you though, something more important, the thing that allows for all of it. Do you remember now?”

“That if I really noticed you, I’ll see it all the way you do,” I answered.

“Yes! Don’t ever forget that mistake. Otherwise Jandee isn’t seen and can’t be defended against because of your fear of death. It is an important mistake to learn from. Now that you are more humble, I have more to show you.” He smiled, winked, and sent me on my way.

Thinking only of him, I reflected on what he had to say as I rode back home, and I understood. If I am the eternal one, then, who has lost their mother? If I am truly love, then the future and past are spent in play despite the appearances of birth and death. Who has gone? Who is it that ever dies? The master was training me to fight for this understanding! He was helping me to see as he did, that sight achieved only by relying on him and not on asserting my self who only dreams from within the rooms of the selfish point of view.

As more years passed to deliver me into my adolescence, my days were spent riding with Darlian, who at age twelve was given his own mehra. He named her White Mane, and she was splendid, her horns long and curled, nearly bone white. She was tan in color and her tail and mane were vibrantly white, and thus her name! Nanui, by default, became my own mehra. Grey with black horns and dark eyes, she was a dear to me. Together, Darlian and I ventured through the jungles of Genia, often engaged seriously in the hunt or traveling in an official capacity along with Minot and his detachment of men, bearing the standard of Arkaya. There was only duty. Our days of reckless adventure in the deep thick were gone.

We rode now, stronger, at full gallop, mehra hooves throwing clods of red Arkayan mud into the air as rain poured against our strong backs! We were bigger now, nearly grown, and our elder brothers Kuba and Seleth shared their duties with us. Darlian and I now routinely traveled the full perimeter of the entire Khoorlrhani circle. We rode along the entire outer fence between Tanaga and Kamina, further east to Isiwa and south to Kushite. We even traveled on occasion to the outskirt city of Ketique where Lord Dajai ruled. That year, I met all the chiefs personally in their keeps and corresponded with their families as was expected of me.

Though there was peace, the talk of civil war among Khoorlrhani was rampant. Dar and I wondered which one of the noble lords would be the first to turn, to cede. Tension was mounting as rumors of my father’s insanity circulated. Though no one doubted the master, the desperate political maneuvering to oust my father had begun.

Consequently we traveled to the outer cities with entire divisions, our arrival a show of Arkayan strength. Then I and Darlian were introduced to the daughters of lords, and talks of marriage proceeded to keep the Khoorlrhani unified. I was eleven then. My voice was beginning to change and I was taller, about the same height as Darlian. It was arranged that Darlian would be married to Lord Tannis’ second daughter. It was then arranged that I would be married to his third daughter, who was only eight years old at the time!

I was shocked by this and resented having to marry for political reasons. My father would not relent, however, and only spoke of my marriage in terms of what was good for Arkaya.

I hated that I and Darlian were Khoorlrhani-Tah’s political pawns, and over time the title of prince seemed menial, unimportant, and unchallenging. I wanted freedom! I began again to complain inwardly and dream of a life of dramatic importance—of my own kingdom if you will.

Disturbed, I confessed my feelings to Minot.

“Give it time. In due time things will make better sense, Jeshoya,” Minot would say.

I wanted to be taken seriously, to hold the reins of my own destiny. Why could I not choose whom to marry like my older brothers?

“Because your father is stingy with the bloodline,” Paen cracked. “He wants to keep the eldest brothers and their families close to the capital, which makes you the scraps he tosses out for political arrangements!” He howled.

Sasojeda, the master’s devotee, sat next to him in the grass beneath the sun, and they both listened to my complaining. Sasojeda laughed as the master teased.

“Scraps, eh? Tannis will not go for it, Sasojeda. Not enough meat, eh? What do you think? Do you see this boy before you as the next Prefect Lord of Kamina?”

“He should have at least offered Seleth.” Sasojeda said, his voice gravelly. “That would have been more convincing.”

“No. You see your tah is desperate and stingy. He never gets how he insults everyone,” the master said. And then he looked at me and said, “Don’t you worry about it, Jeshibian,” as if the writing were clearly on the wall for him see.

I had no eyes for it whatsoever. Paen explained later how afraid my father was, how cowardly this gesture of his was. He had no real faith in the peace. He kept the strongest near him and dispatched the young to sink or swim.

“And he cannot even see that his actions reveal precisely that!” Paen said, and then he encouraged me to let go of it. “For you are with me, and always will be,” he said.

So I then focused much of my potential on victory within ahenyeg, which I still hadn’t been chosen for. I figured that a splendid show of my ambition would speed it all along. I trained with Minot, who taught me fighting techniques late in the evenings. Beginning to take me seriously, he taught me several forms, his best.

From Minot I learned the form of the tiger and the asp. I could twirl the heaviest of scimitars fluidly, and I sparred with my other brothers and competed with them. Then I actually won contests and moved up in standing! I enjoyed the attention from the young girls now, and I no longer shrank away from the circle. It was not long before I became proud unto conceited.

“So now you seem to fit in. What do you want to do now?” Master Paen would tease. “Do you want to now fight a legion of Mayak single-handedly? Will that inform you of your purpose?”

“Yes! I mean, to have enough courage to fight a legion, I think.”

The master threw back his head and laughed. “And you are sure of this?” he asked. “I suppose then you’ll want to choose a wife too?”

I scowled at not being taken seriously. “I want to be like Minot. I want to be brave and strong enough to cleave Mandee and Jandee in two and best eighty warriors like him, like you!” I confessed.

The master laughed more, and then he beckoned me to take a seat on the mat he was sitting on.

“It sounds like Minot told you about all his precious victories, eh?”

“Yes,” I said. Minot then sighed, knowing he was caught. My father, who sat nearby also laughed. I remained on my feet and exclaimed, “He told me all about how you bested eight hundred men north of the gates but you were put in a prison by Toumak! He then told me that you instructed him to finish your mission! I didn’t know that it was Minot who took on my father’s Bakuwella guards, all eighty, and freed you.”

My father laughed harder as did Paen.

“I’m glad you now have humor about it, Boutage-Tah, but is what your son says true, enkosi?” the master asked my father.

My father lay on his side, grinning. He nodded. “All I can say is it was not a proud day for myself or for my army,” he joked. The master laughed loudly and nodded his head. He then sighed. They then seemed like old friends to me.

“Hm… Who did this? I did this? I don’t recall it, really. Was that me?” asked Paen, looking as if he was trying to recall a distant memory.

“Ah, Master, that is a good question. I’ve wondered who could manage such a feat,” the tah said.

I was darkening internally. If this story was a lie, I would be so angry at Minot, and I looked at him sharply.

I protested, still standing, “But I read scrolls, testaments of it in the libraries and…”

“Ahhrgggg… Gossipers will gossip,” the master interrupted, waving his hands.

“I certainly don’t recall doing such great things. I’m but a little old man!” Paen said. My father laughed even more.

Paen then turned to Minot and said, “Minot. I had no idea how much.. fighting skill you had. Why, for you to take on eighty men, and Bakuwella at that, all by yourself. I am astonished!”

Paen, approached Minot, who was dark with embarrassment.

“May I touch you, oh great Prince?” the master teased. “Bask in your brilliance?”

“Okay!” Minot grumbled. “So I did not tell it rightly.”

“Jeshibian,” the master said. “These events have some truth, but there is such a critical omission to Minot’s version of the story, and it is an interesting mistake, that omission, I keep pointing out to you. I hope you can learn from your brother’s mistake here.”

I finally surrendered and sat on the mat by him, folded my knees into my chest, wrapped my arms around them, and asked stupidly, “Omission?”

“Yes. You see you’ve forgotten so quickly already! If you had asked me who it was who defeated your father’s army, I would say, ‘Not me. I cannot do such a thing like that.’ I would say, ‘I can only cooperate with what is bigger, better, and more capable than me, and that SHE did that. She planned it. She made it come to pass.’ Do you remember Nayogi’s story?”

I smirked, somewhat reluctant to follow the thread, knowing that it would only lead to the master smashing to bits my ideas of how I accomplished rank in the anhenyeg or of how I could accomplish anything.

“Do you know what I am saying to you now, young prince?”

“Ashuta.” I sighed, giving in, and smiling as if the master removed my idea, a simple ware, and again placed it on his higher shelves from which he might give them to me later, when I understood more.

“Indeed, and said with such disappointment! He omitted Ashuta! He leaves the divine out of the picture entirely! Only the divine can do something like that. I can only cooperate with Her whim. I can only master the art of cooperating with Her, the art of humility. I am just an emptied vessel ready be filled at Her whim, an instrument plucked by Ashuta’s splendid fingers. So, young Minot, who was it really that moved you that evening that you rush to claim credit for?”

“I told the story out of conceit. It was you, Master,” Minot said, his eyes lowered.

“Yes, and I am no one at all, just an open field through which the Goddess flows. If you’re your attention is on me, then my capacity of perfect surrender is extended. Why did you tell your brother that you did this? Why do brothers do such a disservice to one another, put out this fool’s gold before them to chase after?”

The master only laughed as Minot said nothing. “I know why. To reinforce his idea that he is a great ‘one’ among others!” The master laughed. He leaned forward and looked at me straight.

“You see, the great One is the animator and does the doing as it seems to be done. You all forget this. You wish to possess it and control it. It will not work because in truth there is no separate you. So, Jeshibian, you want to be like your brother, or rather what you imagine him to be, instead of being yourself, noticing what truly IS and going from there. If you would notice what IS and go past the discomforts of seeming to have no purpose, nowhere to run and hide, you might discover something greater about yourself.”

“If you go around wanting to be like someone else at the expense of being yourself, then how are you any different from the first brothers, Khoorlrhan and Mayakti? How will this spell of separateness that has you sewn up ever be broken? This search for yourself, Jeshibian, is absolutely false, I tell you.”

I nodded.

“When will you stop putting mud on yourself to be like the swamp? When will you stop drowning yourself in the lake to be like a fish? And when you are in the lake as a dissatisfied fish, when will you notice how you fantasize about being dry and standing as a man. The grass is only as green as your willingness to love truth to its core. So what that you are still afraid of death, of the snake that killed your mother. I would be frightened of her as well. You are not here to be grand and untouchable, comfortable and pampered, but rather humble, human, and vulnerable, and above all that, mortal. And why?”

“Because you are here to face death.”

“You will get brave because bravery is in you and must come out according to God, not because it should suit your vanity and make you feel good about yourself, but because you need to face your death. It is no instant thing, Jeshibian. So you are still a bit sad that you miss Suwon. Your brother is at least right that in time you will be ready to let go of all of this. Go now, Khoorlrhan, and ride, forget about being so serious and demanding that God make you something else!”

I simply was as unoriginal as the master pointed out to me when I was younger. Being called Khoorlrhan by Paen made me sad with disappointment in myself. I just did not understand, and knowing that I did not understand, my master only told me to not worry, that I would begin to see for myself. He would be there for me once I did begin to understand, and unbeknownst to me at the time, he would give me everything so that I would see.

And so I did ride with Darlian through the jungles, forgetting my disappointments as I made friends, with whom I laughed and struggled. Darlian and I grew closer. We laughed and struggled to be straight with one another. The year seemed to fly by, and soon I was twelve. Still though, I would not forget my ambitions entirely. I found myself still wanting a sign, wanting adventure.

I continued to practice the rites, attained rank in the ahenyeg, and soon Minot initiated me into manhood. I knew that he would choose me for his group, but only after I showed him I was not taking for granted that he would choose me regardless by performing all my duties better than anyone else.

In celebration, I slaughtered a goat and we ate it, and that night a giant drum circle was held. The circle of girls anointed me with ash and each one kissed my cheek as I walked among them, my face painted red around the eyes, large palm leaves tied to my hair. Naked, I passed through a wall of palms and was presented to my father, who sat next to the master.

As was customary, I lay flat, my face to the tile floor, and my hands held up to receive the weapon to signify my rank as a warrior. Usually the one who chose the boy from the circle presented him with his first weapon, a dagger or short sword. I expected to receive this from Minot.

Into my hands was placed not a dagger but a sword, the feel like a scimitar, a weapon worn by a fully grown warrior. Still lying face down, I opened my eyes and lifted my head, surprised by the weight of it. The scabbard was jeweled with complexities unimaginable. I had to blink my eyes before falling into a trance. It was quiet in my father’s court, everyone as surprised as I was.

Was this a joke? I rose to my knees, swallowed, and struggled to straighten myself, my eyes fixed to the brilliance placed in my hands. It was curved, the handle of white beads, turquoise, and diamonds. There was a murmur. Everyone knew this blade.

“Do you recognize the warrior before you?” Paen asked Minot who grinned proudly at me.

“I recognize him,” Minot said, and he beckoned me to stand.

It was my father who usually initiated the warrior, not Paen. Paen typically never had anything to do with this ceremony.

“Jeshibian,” the master said, his eyes ablaze, his gaze burning into me. “This is my reflection, Maburata. Never forget her. This is your duty. Do this and you will see the face of God in all beings. This is what a true warrior does. Never forget your duty, warrior.”

I trembled. I was holding the master’s very own weapon! I looked into the eyes of Paen. My head felt full, my attention focused. I looked back down at the sword unbelievingly.

“I…I will not forget, Master,” I said. Such a gift, the master’s very own Maburata! I trembled beneath its weight. I never expected to see it twice, let alone hold it and much less have it presented to me. My arms shook, holding the weapon. I was in shock. The master nodded for me to unsheathe it.

I pulled the white leather scabbard apart from the handle, and with a chime, Maburata glided out. It was like the sun rising as she slid out of the sheath. The blade vibrated, rang, and shone with white light. The room was alight with her. The master nodded and winked at me. I loved the master, and Maburata betrayed my love for him as she glowed, getting brighter.

Khoorlrhani-Tah rose and held his hands up, and everyone cheered.

That was the day the master made me a man! In truth, Maburata, the master’s sword, was given to him by the Goddess Ashuta. He told me that it was his reflection of loving her. He said that to look at Ashuta’s face, to wield her blade rightly, you must let go of yourself entirely. When Master Paen held it, Maburata’s light was blindingly white, so hot that those who beheld it could even disappear. That is what he told me. He told me also that to behold such purity would disintegrate one’s ego, outshine it. I was dumbfounded as to why he gave me that sword. What did it mean? I could not understand at the time, but beloved Master Paen loved me so perfectly that he would give her to me so that, if I could not let go of my fantasies, he would walk me through the halls of those fantasies guiding me to the truth.

“What, you want I should take Maburata back? Suddenly you don’t want to stand for anything real?”

“No, Master. It’s just that everyone is jealous and thinks I’m so unworthy, and yet I think I am and it makes me feel…strange,” I said.

“Ahhh! I see, but you always feel strange, if you’d but notice, and it’s not your unworthiness that has you feeling this way.” That quip stung, but the master quickly moved onto other points.

“You assume that everyone was not jealous before you ever held Maburata. Everyone is jealous all the time, and angry all the time, and sad all the time. Maburata did not make this happen, nor did my giving her to you. Maburata, which is my reflection, only made this world and this dream of it more obvious to you.”

I did not think of that. I was quiet for some time as I stared off into the distance.

Days later, we rode into the jungle, I on Nanui, the master on Quanon.

“Maburata is not only my reflection but a reflection of what is truly seen. It makes you uncomfortable to see what is really happening here, doesn’t it? It scares you, doesn’t it?”

“Yes.” I could not argue. I could not escape the sense of humanity’s frustration and the fact humanity is woefully lost. I could not escape my own feelings of disappointment, anger, and humiliation.

“Why does it scare you?” he asked. I had only had the sword a week and already saw so much.

“Everyone is really unhappy, but no one addresses it.”

“And?”

“There is nothing in this world that grants lasting happiness or meaning. It all only persists to goad us as something, things or people, to desire, to covet,” I began.

“To be jealous of, and that is why being a Khoorlrhani prince seems to be only an empty title to you, doesn’t it?” Paen asked.

“Yes,” I said.

“And that is why you are scared, because along with the rest of humanity, you know that beyond transcending yourself there is nothing to ever be happy about. Depressing, huh?”

“Yes.” I sighed.

“Good. Ha! Well you must look deeper, my young prince. There is more to see. If you look you will see that there is a choice you can make, to know the truth and accept it or to not accept it. With truth, there is hope to transcend this nightmare as I have, and without it, well, it gets worse and you will feel more tightly hemmed in.”

I carried Maburata with me all the time and never forgot that she was in my care—or perhaps the other way around. I strapped her to Nanui’s side and would go to the woods just outside our dihj and unsheathe her. She responded to me, glowing brightly.

One night, alone in the room I shared with my brothers, I looked into the blade to see my reflection but no one was there. I turned her over and looked at the other side, still no reflection.

I must be doing something wrong, I said to myself.

“There’s no reflection because you are really no one, Jeshoya,” Minot told me, having stepped into the room without my hearing him.

“You take that back, Minot!” I said and stood over him in a rage. I was a warrior after all!

“Calm down and let me explain.” But before he could, Boutage entered our room. The air seemed to compress with his depression. As he walked by he grabbed Maburata from me and unsheathed her. She did not glow, but there was Boutage’s ugly face staring back at him clear as day. He bared his teeth the better to see them, and then he sucked them clean and belched.

“I see my reflection. I guess Minot is right. You are nobody,” he said and then tossed the sword back to me. He went over to his mat to remove his armor and helmet and instantly fell asleep.

“Boutage.”Minot growled as I ran out of the room in a panic.

I rode to the master’s dihj. He was drinking tea and waited outside the entrance.

“Jeshoya!” he called affectionately. “What brings you at this hour?”

“Take Maburata back, please,” I cried.

“Why?” he asked.

“Because I want to be somebody,” I pleaded, somehow feeling that Maburata was a death sentence. I did not want to die!

“But you are somebody. You are Jeshibian Khoorlrhani, the young prince who has five brothers and a sister he loves dearly. You are Jeshibian, Minot’s favorite brother! You are Jeshibian, who we sometimes call Jeshoya because we love him so much even though he hates that nickname! You are Jeshibian who is so thirsty to know who he really is that the sword of truth tells him exactly that, the truth of who he is.”

The master chuckled. His eyebrows were wild above his large beaming eyes and wry smile as he approached me.

“You are Jeshibian Khoorlrhani who wants to be a real warrior. Hmm. Since that is what he wants, how can a warrior that is no one in particular be a warrior at all?”

I still did not understand. I was offended and shook my head. How could I be nothing? How could that be true? How could that be acceptable?

The master took Maburata from me and unsheathed her. The glow was indescribable. When it subsided he walked over to me and lowered her to show me that there was no reflection of him either.

“What could this mean? Why, I am the master, the master warrior even, and yet I am revealed to be no one as well! I guess I should get depressed, eh? Perhaps we can be drinking partners!” Paen mused, poking me with an elbow.

“Does all this mean you cannot play your part as all those other things, the boy prince, soon to be a great warrior etcetera, etcetera, and that you just should contract heavily upon yourself in self doubt and not accept it? Why, if I, master warrior, etcetera, etcetera, can accept the same information about myself, being nothing, no one at all, and still play the part of Paen, who is happy, who is kind and loves you dearly, what is it about you that has you holding back in such doubt?” he said, and with that, I dropped my head into my hands and wept happily, finally getting his joke, this wild prank he was playing on me! All was given but nothing meant anything, even my own appearance, my newly recognized status, and the stages previous to it. The master would give me his very own sword to show me how meaningless it all was.

Needless to say, I calmed down eventually, the master laughing at me between sips of tea, his eyes dark crazy orbs beneath his thick eyebrows. He sheathed Maburata, handed her back to me, and then brought me tea and we sat in his home. I sat in silence contemplating him, wondering, Who are you? I did not leave until morning.

When I carried Maburata on my travels with Darlian, I watched the world with different eyes. It seemed clear to me that everyone is asking the wrong questions. Instead of asking how could I be nothing, I should have been asking how could I be something? Boutage, my brother, assumed and believed in his “somethingness” with the greatest conviction. He had little or no thirst for the truth that lay beyond that assertion, and so he appeared clearly along Maburata’s length. There was absolutely no question of it. What do I believe then, I asked myself. Am I Jeshibian? Am I light?

Life suddenly began to take me on a different journey. I became more comfortable in my quiet nature and realized how my worriment was basically my demands eclipsing the very freedom that Paen showed me as my true nature. And so from time to time I enjoyed this glimpse of Paen’s quiet spaces where no on existed to register a complaint against the world. Who is uncomfortable anyhow?

We fished one day. “Yes, and you believed if you are uncomfortable it is somehow linked to your not being yourself!” The master howled, recasting his line from the river bank.

“How can you be yourself, really? Have you figured that out? What self are you being other than the one who is alive in the midst of an uncomfortable real life? Who do you find when you are in fact comfortable and only get what you want? The same one who is there when you are uncomfortable. No one! The only thing you can do is be mindful and accept the terms of real life. Otherwise you manufacture the who and his entitlement to comfort,” the Master told me.

“But you once told me to be myself As Is,” I challenged him.

“True, but the Self, not the self.” He gestured to accompany the words, his arms first spread wide and then barely spread apart. There is a difference. The one I refer to is the superior, all-pervading one that stands before the person you dream of as yourself, the one that seeks as though something stands apart from him. The One I implore you to be is the same One that I am.”

“Are you ever uncomfortable?” I asked

“All the time. This experience of form is mainly bothersome, and being among those hopelessly bound to their ego does not make for good company.”

“Master, what do you do that you are so happy?”

“Jeshibian,” he said. “In life, there is only doing your duty to ensure survival and to cooperate with the others here. Happiness is already happening if you would only notice it. Do your duty and do not make your ordinary life obligated to fulfill you. It will never work, trust me. I appeared only to serve a function. I only do my duty, so for me happiness is already the case, independent of experience.”

“What is your function, master?”

“To clue you in on the truth.”

“That no one is anyone?” I asked .

“That there no one in any world who is not God already right now and at this instant, that no speck of dust, mouse, mite, beetle, bird, monkey, mango, fish, person, man or woman, rich or royal has been abandoned, forsaken, or forgotten. It is all ME, my bright sphere, all God, all love.”

He told me more about his enlightenment, about what it takes to see with diamond eyes as he did. I only wanted to be with him. He would send me back home though. One night he said, “Keep Maburata for as long as you like, and do not worry about anything ever. Your attractions will move you and guide you. I’m always there.”

I did not know what that meant, but I felt that this was only the beginning, the tip of the iceberg of what he had to show me.

Discussion ¬