Dharmic Sci-Fi Fantasy: The Last Khoorlrhani Warrior – Chapter 3-4

Dharmic Sci-Fi Fantasy: The Last Khoorlrhani Warrior

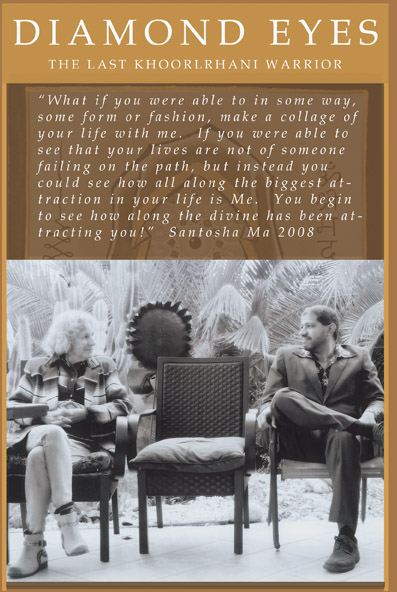

The Last Khoorlrhani Warrior, is the second in the series of novels written for the Diamond Eyes series. It centers on the next generation of Khoorhani, whom Paen of Eastern Genia serves in his role as the Master. I’ve posted the first nine chapters out of about thirty three. Use the menu below to read the first nine chapters, or scroll to the bottom to download a copy. Enjoy

The Last Khoorlrhani Warrior, is the second in the series of novels written for the Diamond Eyes series. It centers on the next generation of Khoorhani, whom Paen of Eastern Genia serves in his role as the Master. I’ve posted the first nine chapters out of about thirty three. Use the menu below to read the first nine chapters, or scroll to the bottom to download a copy. Enjoy

Chapter 3: The Master

I remember that, as a baby, it was Master Paen who stood out to me among all the blurry shapes and forms collected around me. Master Paen was a bright light, and I remember as a child being only attracted to his presence. Somehow I knew him even as a boy with no experience to call on for any memory of him. I knew him, and I knew that I knew.

Master Paen was bald, his reddish brown face round with small features. His eyes were deep brown and they looked deeply into one’s soul. Master Paen was not a tall man. In fact he was at least two heads shorter than most men. Still, when the master walked into the room, all eyes met him. Many longed for a moment of his attention. He was quick though, and one had to work hard to keep up with him. He was not waiting around to receive special recognition from anyone, and he was largely unimpressed by most, though his compassion for others was always demonstrated perfectly.

When I was very young, Master Paen often traveled with my brothers, Minot and Boutage. On many occasions Paen was accompanied by two trusted friends, Banwedo and Sasojeda.

In those early years, Paen’s business seemed mainly in tending to my father, working ceaselessly to release him from a spell that, as my brother Minot described it, had worked to strangle the spiritual wisdom out of the kingdom.

To one not looking closely, it appeared that the master was a mere advisor to my father, but my mother, Suwan, and my brothers knew otherwise. Their knowledge was marked by hushed conversations about Khoorlrhani-Tah and how Paen was saving my father’s soul, somehow unbinding his heart and mind, setting him free.

Paen was like fine grained sandpaper, smoothing, softening our hard edges, our stubbornness, and teaching balance to the impatient and afraid adolescent that my father was in spite of his years. Paen would spend great periods bringing the heat of exacting criticism upon him.

They would argue, and then Paen would disappear for weeks, leaving my father alone to consider a slowly penetrating lesson. Paen’s work was never ending.

Because of Master Paen’s prowess and grace, and because often times Paen would travel to the other cities, including the territories of the Mayak, my father, like a possessive lover, would become disturbed unto paranoid and could not repress his tendency to be a war monger.

“I test his limits so that he will release his grip, that he might stop taking up the cause and instead lay it to rest. I have tried to wear down his narrow perception so that he might enjoy the spacious heart of the real. I drag him out of the swamps of his tightly wound mind so that he can begin considering the real matter at hand.”

“What is the real matter?” I wondered aloud.

“That the true king serves by sacrifice of himself entirely to the divine. The TRUE king neither rules purely by the politics of self preservation nor does he purely rule by the rigid laws of tradition. HE only rules by adhering to the ultimate law?”

“Ultimate law, Master?” asked I, a short six year-old boy looking up to the illuminant One and wondering why my father was so angry at him.

“The first and ultimate law is that there is only Ashuta, God’s kingdom, my kingdom.”

And my father could not argue ultimately against the master. Why?

Because ultimately he knew the master was precisely that, the divine, God. Though his ego struggled to accept this, he knew the master to be true for, by Ashuta’s graces, the master single-handedly defeated every last man in my father’s army. I could not comprehend what this battle might have been like or imagine the master in this way, but the story was as fresh as yesterday’s news and still glowed in the hearts of those who loved Master Paen.

Like my father, the entire kingdom struggled as we were preoccupied with the example set by our tradition. Before the master came to Arkaya there was war. During my great grandfather’s reign, the Khoorlrhani pushed the Mayak into the mountains and took the land.

During my father’s reign, an enormous stockade fence was built around the capital city, a structure made of large sequoia trees imported from the west. Before the master, there was endless war.

Soon after Paen’s return though there were the soft delicate breezes of peace and truth. There were no more awful battles in the northern territories. There were no flaming arrows shot from the towers of our gates at the masses of Mayak that stormed Arkaya and the satellite cities. Minot told me that, after all the turbulence ceased, I was born.

Master Paen often spoke to me without words, and in fact with only a glance, and thus I knew him to be the great one, the real chief, the real tah. In his company I was given the benefit of knowing this, unchallenged by my father’s hollow claim of divinity. My father was only a poor representation of what the tah used to be in times of antiquity. The master’s work was to change that, to bring wisdom to men and demand that they be accountable for that gift. I knew all of this even as a babe who had no language to express it, no historical references to draw from, and no need to have it proven like it was to my father on the “battlefield of his ego,” as Paen put it.

Minot told me about his first meeting with Master Paen. As a young centurion under the tutelage of Lord Dajaai, Minot actually faced Paen in battle in a naïve attempt to protect our father and his kingdom. As the story went, my father was terrified after hearing the stories from those who rode home to Arkaya warning Khoorlrhani-Tah of the traveler claiming to be the master warrior. It was said this warrior was on his way to see my father unhindered by wave after dispatched-and-thwarted wave of defenders sent against him.

“He feared the arrival of God, the arrival of truth,” Master Paen said. “But it was my mission, since he wore my crown, to bring the truth to him even if he resisted.”

“My father is afraid of the truth?” I asked.

“Most men are.”

Though he was often described as the most proficient sword master in all of Arkaya, I had never seen Master Paen handle his sword, Maburata, nor ever harm a soul. He was mainly gentle and smiling with eyes that shone like diamonds. Still the stories of his arrival were miraculous, fantastic and inspiring! There is also an archived testament of that day recorded by those who met the master in the fields as he approached. It reads as follows:

We sat in a circle to share the memory of the master’s return to Arkaya; and of the master, Dudo of the eighth infantry said, “When he rode down the hill toward us, I thought, for a moment, ‘One man? All this fuss over one man and all these men arrayed against him?’ But our commanders were as serious as sin and that rallied our hearts, created a mystery around this one-man-army before us.

“And then I and my comrades formed up, one line out of six horizontal lines of forty mhera men, THAT’S TWO HUNDRED AND FORTY MEN, ready to smear this buffoon right into the grass with our scimitars.

“I don’t remember much after that, only a brightness beaming through the clouded darkness of us, our stinking mass of armor, leather, metal, and mehras. I recall only that and coming to, this small man helping me back up. He whispered in my ear that it was all over, and he did not refer to the battle that took place on the field but the one that went on in my mind and heart. He showed it to me first by striking me on the back and then on the sides with the flat of his blade. I have never loved another man so much, never. He then showed this utter mastery to me again in the profound clarity of his company—so radiant.

“Ask any man in my company and they will tell you what kind of a man I was before that day. After that day all of us were in awe of such purity, such grace, such bravery to step into that thorned forestland of our bitter hearts to show how false we were, to show us there was something more profound and real to serve and love.”

Of the master, Sasojeda of the seventh infantry said, “The truth is lightning hot! The master is just like this, lightning hot, as well. He obliterated us, tore us to pieces. I’m talking about our pride, our egos, even though literally he made a nice pile out of us too! He made it so that our hearts could not avoid his message that only Ashuta is real and our ways are limited! He proved that this higher power is reality by his demonstration of complete abiding in it and his riding alone against us, destroying us, and yet somehow sparing us all except those who’s refusal was so extreme they died of their own exhaustion! What a paradox this was! They would not believe it, could not, that this lone man with no armor, just sandals and a gleaming sword, defeated whole armies and smiled while doing it! We poured into him like a whirlpool, and he spun us about, around the shining center that was him! The outrage! Arkaya would not have it! And yet there he was, not at all worried about what Arkaya thought.”

Of the master, Banwedo of the second Ketiqan infantry said: “Of course we were offended! I was beside myself with offense. I rather think that Paen of Eastern Genia is the master of offense to the ego in its uselessness, its pride and concerns. Like Sasojeda testified, I saw who beloved Master Paen was once I was face to face with him, and I immediately dropped my sword. Even if I could have, I would not kill this man. I was looking at innocence, a bright form incapable of doubting itself because it yielded to the heavens. I was looking at innocence, a bright form never capable of doubting his steps. He would not fall! He was victory itself. I thought, ‘I will go mad if I do not surrender to this, if I do not understand what I’m seeing!’ He winked at me, and then he tended ferociously to the other combatants. I dropped my blade. Though his mouth did not move, I heard him say to me, ‘Now if you can keep your hands empty for the rest of your life you will understand completely!’ And now every time I see him in the palace, he reminds me of how I took up my blade with him. He says, ‘Each time you assume your role as a separate being and take it on with such seriousness and with all your petty little plans, you defend yourself against what I have to teach you, that you are God! Empty your hands, I say, and take eternity for yourself.’ There is no question. Paen of Eastern Genia is the master, is Kalid, and is truly the tah.”

I would beam as I read these texts in our library! My heart would want to leap out of my chest! When I saw Paen, I yearned to be by his side and was overjoyed to find him nearby often. It was as if he always had one eye on me, making sure that my flame for him was never doused by the cruelness of our times.

He stayed near to all the Khoorlrhani children, particularly the youngest, my twin sisters Anaya and Lenya and my brother Darlian and me, all of whom were born after the master returned to Arkaya.

“I think Jeshibian, here,” he would say, “would like to know my secret. What do you think, Minot?” he would tease my older brother.

“We all would like to know your secret, Master,” Minot would say as he picked me up to take me with them in their travels.

“Oh, that’s just talk, Minot. I don’t think you really do.” He would tease my brother, sometimes rather harshly; and in those moments, I did not understand why he said what he said to any of us. But I remember the heat from the fire of his wisdom purifying us, and now I can see how the master was sanding down my brother’s ego and my own as well.

Of the master, Captain Minot of the second Ketiqan infantry said: “I set out against him after my first defeat. I would not have it. I would not lay my causes to rest; I would chase him. I recalled what he said to me in Ketique, the rain pouring down on me in my defeat: ‘The harder you fight against what is true, the more the truth must obliterate you!’

“I traveled in search of him, dead set on intercepting the master and derailing his plan. Then, on my second day of spying on him, I unfolded at his feet. I fell in love and was obliterated by the truth. Paen and I rode together into Arkaya, and my father, who was angry, jailed him. Paen submitted and I did not understand! Why? He demonstrated perfection in battle, and now, before the tah, he offered his own hands to be bound. I would not have it, and so taking up my cause, I battled my father’s Bakuwella in court so that he would finally hear.”

“But as soon as you have a glimpse of Her face, you make it all about yourself and lose the bigger and brighter picture beyond that point of view!” Paen chided.

Just like my father, Paen criticized Minot as well. He did well to point out Minot’s conceits, to leave him unable to refer to himself in grand terms, as he tended to do.

As my brother told me, the master took our kingdom, and in doing so, everyone saw that he was really the true tah, but he did not remove my father. Why? Instead he drew a line for my father to live up to.

He lectured my father, beginning thus: “When you seized power on that fateful day…” The implication was in regard to the catalyst event that required the master’s return. My father murdered his own brother, Master Kalid, who reincarnated as Paen to march back to Arkya and reveal to Khoorlrhani-Tah the futility of ego against the power of love.

“When you seized power you created this karma, this burden of ruling as I would. The true tah cannot have ego. I am here to help you face the death of your ego and not resent your karma, to help you do your duty as a true king. I believe you can do this. I allowed you to kill me so that now I may kill your ego!” Paen then laughed while all others present were quiet and held tightly in their stance against him.

These words stirred the hearts of the chiefs and warlords, those beneath my father, who whispered in private, their calculating minds trying to anticipate where grabs could be made within the shifting balance of power as the question of my father’s sanity was raised among them.

If the tah took council from this outsider, as they saw Paen, what did that spell for their future as prefects? The chiefs of the north whispered among themselves, preparing for the worst political arrangement in the history of the Khoorlrhani, whereby a foreigner (in their view) gains sole influence over the throne.

“Do this one thing, submit!” the master said. “Align yourself with me and you will be happy to learn who I really am, who you really are. Make TRUE use of me and you will see the big picture, and then you will laugh from the seat of your real self. You will be happy!” Paen implored my father.

Otherwise, having no purpose to be among us, the master said he would retreat into the lands from which he came, leaving my father to his own devices, his old habits of defense taught to him by the fear mongering and deception of the entities that had possessed his heart for decades and motivated him to habitually assert his separateness.

“Suffer that,” he said, “and you will only know chaos and the need to understand your evil deeds without the divine means to do so. Joy will be veiled from you, and for fulfillment you will resort to the world—the one that you already know is empty of fulfillment entirely.”

Needless to say, my father chose the first option.

Chapter 4: Khoorlrhani-Tah

My father spent most of his time on his throne, his brow always bent and heavy as he sat holding his head on one hand, a supporting elbow against the ivory armrest. As I said, he and the master often argued, and always in the courtroom. And most of the time all those in my father’s court were present to see the master’s unending work of freeing my father and purifying the kingdom of not only my father’s influence but that of previous generations. As a boy, I did not understand the arguments to the word, but the gist of them never left me.

They often times went on like this: The master would say, “I cannot make you stay here, here in this heart of me! I cannot force your hearts and minds to stop their search for that something that does not exist, the happier-than-already-happy circumstance that you keep hoping for, these Holy Grail-cure-for-pain ideas you chase after! I can only be nearby so that one day you grow tired of chasing after experiences to get fulfilled, so that you catch your reflection in the mirror pond and see your silly dance of chasing your own tail like some silly monkey or shamefully hiding your tail as though you are the only monkey in the world with one! That dance is what you are suffering. You are doing it in this search for power.”

“You swear by the stars that you can become ultimately fulfilled by some supreme act of dominance or by political arrangement, but you don’t understand how it is just making you…insane! And look how the other monkeys do just as they see you do, taking up arms, climbing the ranks!”

“You are not the power! You are nothing. She who is all things lends power to he who is humble enough to receive it and willing to live by that emptiness alone, that vulnerability wherein love has a chance. Your conviction that you are real only reinforces your habit of defense!”

“You must go here with me, brother, and consider what I am showing you. Don’t you remember this lesson? It is the same lesson I’ve taught you, the same lesson your brother Kalid taught you! Have you no ears? Have you forgotten me, forgotten our walks through the halls, the woods, and into the mountains where I taught you with my arm slung around your shoulder while you stuffed fruit into your face? Have you forgotten when you were a more reasonable man?”

And my father would gnash his teeth and sigh.

“What am I to do, Master!?” And the master would laugh at him and look at him so lovingly, but he also looked at him with disbelief as though Master Paen had said what he was about to say to my father a million times already.

“You haven’t noticed what you are doing! You’ve tightened that vice you feel your heart squeezed by, but you swear you had nothing to do with it. It is the dance of fools. When you are done dancing, you may finally see me, but for now, we dance. You don’t see me, and therefore you don’t see yourself!”

“I say that you are eternal, and you say, ‘Yes, Master Paen, I know; and this is how I know…’ You agree that you see and then you go on to assert your personal power rather than express the wonder of what true power is! It is a wonderful power that breaks you open so wide that you cannot possibly carry on so seriously the way you do, justifying, defending, and lamenting all the time! If you really knew, like you say you know, you would happily throw yourself to the floor upon sight of me. And you would give me that damned crown because you would have recognized me and seen that you have no use for it. You would kiss your servants, your sons, and daughters instead of leaving them unnoticed as you toil away at your Sisyphean task!”

It would be quiet for a long time as everyone in court seemed to hang on Paen’s words, which seemed to have taken the place of is sword. Then he would pick up again.

“What you say to me is so blahdy blah blah blah! You cling to the most threadbare evidence as though it really can explain a damn thing! You understand nothing! You are eternal, all of you, but you are completely oblivious to that fact because you don’t account for how you reinforce this feeling of your separateness, driving it like a wedge into your heart. So again I say, there is no YOU! If you recognize that you indeed are eternal, then what is there to explain to the same One who sits before you? Shouldn’t it all be obvious? Shouldn’t the being quality of eternity BE enough?

“Who, pray tell, are you explaining all of this drama to? I do not assert my me-ness over here. I tell you there is no person here ever! We must move on from this. You always pretend, brother, but still you are not willing to give up pretending to be a king in order to BE that which is truly greater: eternity itself. You never give me a chance! You are eternity, but you want a crown to tell you who you are! Do you get how silly this is? Only when you are emptied of your point of view do you truly wear my crown. Until then you are full of delusion and suffering from it. When will you be still and meet me, see me, love me, instead of Arkaya?”

Sometimes my father would nearly cry. He seemed touched but also trapped by a long karmic yarn he had tangled himself in, as were we all.

My brothers, sisters, and I had our father’s hands: wide, thick palms, long fingers, the same broken “m” shape in the center, the same veins on the back. Khoorlrhani-Tah’s shoulders were wide, his neck long and thick, his chin narrow, and his jaw slightly square. His eyes were sometimes like red bits, windows to a methodical mind, intelligent but stubborn. He often yelled at servants, but then he made gestures to be forgiven. He meant well but only knew tyranny. He was tall and somewhat muscular, and he often wore the traditional face paint, red vertical streaks across his eyes when he sat on his bench brooding, arguing, and ordering.

Though we were the honored family of all Khoorlrhani, our dihj, our home, seemed haunted by disappointments. As Master Paen criticized our father, we all seemed distracted, not even exhibiting a sense of ordinary happiness because of our more luxurious circumstances compared to most.

The master would say, “You have survived the jungle and the beasts and have shelter. What else is there to obsess about? Becoming exalted as warriors? Nonsense! You are just as silly as your father.”

It was easy to blame Khoorlrhani-Tah for our suffering for he was the king of all suffering egos, an easy scapegoat, but as Master Paen put it, Khoorlrhani-Tah was the example of all our turning away, of all of our self involvement and our search into the dark woods for that which does not exist.

“You are all co-creators. You are all doing what he does. Do not be mistaken.”

Khoorlrhani-Tah made a mockery of the crown in the same manner as my brothers and sisters and I were a mockery of our titles as princes and princesses. We all assumed Paen’s words were directed at the others, never placing the target on ourselves.

Indeed, my father’s search twisted his heart and soul, and his reign twisted the hearts and souls of those who were aligned to him for we were aligned to his design, the design handed to him by his forefathers.

“No! It’s your fault! What happens right now is your fault!” Paen said, “You must wake up and choose! You are not simply the victim of your traditions! Will anyone be brave enough to stand against them?”

I did not know my father as Minot and my other older brothers did. Though I felt the violence of his soul, he neither raised a hand to me, nor was his indifference so insufferable. That said, though, I only saw my father during the formalities of his court proceedings, which I was taken to sometimes and other times spied on. My father seemed a stoic figure mainly, who’s wealth provided me with immediate cultural status as well as a well made vine and clay roof over my head and plenty food. His kindness was even expressed, albeit awkwardly, from time to time.

I would find out later that it was Paen who advised my father to only formally relate to me, which was in fact one of the conditions of his staying in Arkaya and not retreating into the jungle.

Discussion ¬