Dharmic Sci-Fi Fantasy: The Last Khoorlrhani Warrior – Chapter 7-8

Dharmic Sci-Fi Fantasy: The Last Khoorlrhani Warrior

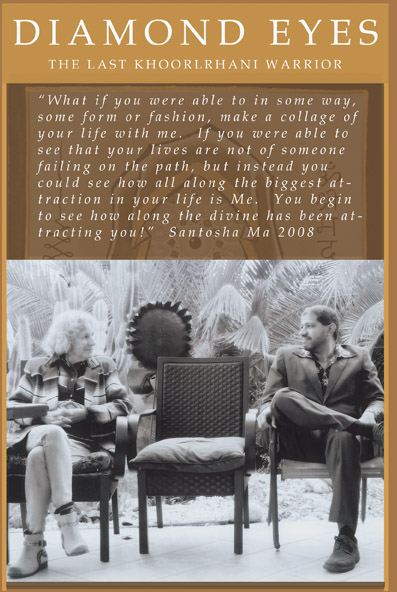

The Last Khoorlrhani Warrior, is the second in the series of novels written for the Diamond Eyes series. It centers on the next generation of Khoorhani, whom Paen of Eastern Genia serves in his role as the Master. I’ve posted the first nine chapters out of about thirty three. Use the menu below to read the first nine chapters, or scroll to the bottom to download a copy. Enjoy

The Last Khoorlrhani Warrior, is the second in the series of novels written for the Diamond Eyes series. It centers on the next generation of Khoorhani, whom Paen of Eastern Genia serves in his role as the Master. I’ve posted the first nine chapters out of about thirty three. Use the menu below to read the first nine chapters, or scroll to the bottom to download a copy. Enjoy

Chapter 7: Warfare in Brotherhood

And after a while, though haunted by the initial telling of the master’s tale, I did not worry so much. I carried on in my assumptions, moving toward the paths of Khoorlrhani zeal along with my brothers. Soon I played with sticks, our swords, with Darlian, play fighting and imagining my own greatness as a Khoorlrhani warrior.

It was customary for boys older than nine to gather around a bonfire beneath the starlit sky. Some of the older adolescent boys would tend the fire while others beat large drums and formed a circle. Nearby, the girls gathered to dance and sing, and the boys would call each other out and fight with training swords.

This formal occasion of challenge among the youths was called ahenyeg, which means yield. This was how young boys would eventually become fighters, and some, those not already arranged to marry, husbands. Those who won the contests were acknowledged and usually taken under the wings of the older boys, young captains who led light patrols around Arkaya, guarding our crops in shifts alongside older, more mature soldiers. The most accomplished of these captains would get first choice of who to add to their group, their ahenyeg. Both Boutage and Minot were captains, and the most popular.

During ahenyeg, the contest was simple: stay in the circle and defend yourself against your opponent. Points were given for good clear strikes. The one with the most points won. If a contestant ran out of the circle, they lost. Those who lost kept developing their skills, hoping to be accepted. Those who won participated in the next level of the competition, fighting members of other captains’ groups in games such as conquest in which each team must defend a herd of cattle from the invading teams who tried to steal them. There were also variations of this game in which the object to steal or defend was a mere flag. The campaigns would go on in summer heat beneath the moons once a week. The games went to dawn until winter and the rainy months.

I did not participate happily. Uncoordinated and generally timid, I did poorly. I felt ashamed as my elder brothers watched me “continually lose to lesser families,” as my brother Boutage put it. I started out confident, but then I would find myself on my back outside the circle and eating the dirt dealt to me by my opponent!

Minot, always sensing when I was on the edge of giving up, would pick me up, brush me off. and say, “Jeshoya, it does not matter. It’s just a game, and that is the point of being a warrior, to not give up. Stay in the game. Stay in the circle.” Minot always encouraged me this way.

How could a Khoorlrhani prince be so obviously bad at holding his own in a fight, I wondered? I was terrified that I was inherently a coward. It was then I became sensitive to being called by my nickname, Jeshoya. It irritated me to hear it from my brothers as though it implied I was a simpleton. It made me feel reduced. I did not recognize that what the master had been telling me about Jandee was playing out in the slow boil of my life. I did not note that the spell of self-imagery was taking shape within me so strongly.

During the peaks of my frustration, I would avoid the circle and I told my mother, “I would rather be with you most times. It’s quiet and there are plenty of interesting things to do.”

My mother would laugh, draw me near her as we walked, hold me to her side, and sigh. “Jeshibian, you can’t do this your whole life. You cannot avoid what is uncomfortable. In life you must fight, and you must endure the fighting of others.”

She nudged me away, toward ahenyeg, the circle of boys. I tried my best to do what Minot taught me: “Keep your guard up, watch your hands, focus, block, watch your head…” But I was awful, getting black eyes, split lips, and torn clothing from savage opponents who had much to prove against a Khoorlrhani prince in the open circle! I loathed it, and then eventually, I slipped away.

Minot would let me go, saying, “Cool off. Don’t worry, Jeshoy…ahhh…er Jeshibian! Come back when you are ready.”

Gone were the blissful threads of morning-light abandon, and instead I awoke to each day as a problem. I worried that I would never grow, improve and rather suffer greater insult in the circle. .

Away from the circle, I spent time basking on the rocks trying to forget about it, making Anya laugh by crossing my eyes or searching the nearby thicket for insects, my hobby of sorts.

In the evening, I could hear the aunts and uncles whispering. “He clings to his mother still,” Toumak said to my father, and I knew my father’s opinions of my talent.

“Yes, a bit soft and scattered,” Khoorlrhani-Tah would mumble. “Perhaps he will grow out of it.”

“Suwan will spoil him if she keeps indulging him,” said Toumak in the dining hall where my father ate only with his general.

“They are right,” Master Paen said one day. “You cannot hide from life.”

“But you said that I should do what I want,” I protested.

“True, but you must have balance. You must do your duty, and you must face your fears. You should want to examine yourself here!”

“But I’m so bad and everyone laughs.”

“Do you see me bent out of shape because no one, not a single soul in the kingdom is interested in enlightenment? Ha!” The master roared with laughter, slapping the low table top that we sat before in his dihj where I often visited him. His laughter was so loud that parrots in the distant trees mimicked him. I only grimaced and averted my eyes, now a stubborn nine-year-old.

“Do you hear me going on about how bad a master I am? Ha! Oh, that’s funny! What if one day I decided to not show up? Would that strike you as odd? It would be strange to you if Ashuta herself appeared to me and I went on saying, ‘Boo hoo, great Goddess, the tah and chiefs laugh at me because they don’t believe in enlightenment!’” He teased me mercilessly until I relented and began to laugh with him.

“Fighting is simple, and it is not personal. Face your opponent. Face him. Who cares who wins for who is winning anyway? That’s the most interesting question there! You’re not using the tools I have given you. By facing it head on and not trying to escape, at least you will discover if you can fight; and if you really can’t, then you can explore other options besides fighting. Running is not the answer. You see, you want a victory and are embarrassed by defeat, and now you look to your mom and me to do what? To fix it for you, to hide you away and keep you safe! Who are you anyway that a victory or defeat matters? Who does this mistake of assuming a you remind you of?” he chided.

“The first princes,” I replied, now seeing my mistake.

“Yes. So stick close to Minot and just do the best you can. Oh, you are a worrying soul, aren’t you, so desperate to fit in? I’m telling you fitting in is a confinement. Do not worry so much.”

I did what he told me and eventually learned what it meant to hold my ground. Eventually I came to understand and enjoy an aspect of myself that I and others assumed was not there. With green face paint around my eyes, I accepted the circle of the boys and soon I enjoyed the passion of the booming drums, the chanting girls, and the shouts of the other boys. This did not mean I was a champion by any means, and during my worst defeats it was still my tendency to run to my mother.

Still, with Paen’s teaching, I accepted my place among the boys, and with my insides uncoiled a bit and with coaxing by my peers, we adventured.

Minot and Boutage often promised, threatened more like, to take us beyond Arkaya’s gates, far to the north to the Nook. This was beyond where the outer stockade was complete and minor skirmishes broke out from time to time. My father stopped building the outer wall when the master brought him back to his senses, a topic Boutage and Minot never stopped debating. The outer wall, a very incomplete circle and an insane undertaking as it was, only met between the cities of Kamina and Tanaga. There was only a portion a few miles beyond both cities, its use now only as a large watch tower to see approaching Mayak should they ever plot to invade our cities again.

Boutage and Minot often romanticized making a trip to this wild area. Though they were more responsible now, their rebellious side often gave way to these kinds of plans, to dares and to double dares. They were not stupid though, knowing that, as heirs to our father’s crown, they should not endanger us all by pursuing foolish games. They planned for months, and then one day they came crashing into our quarters to tell us, “We’ll go tomorrow!”

We made that first excursion with perfect execution, and we enjoyed ourselves and each other’s company, and so we made a ritual of it. Our camaraderie was strong, each of the terrible six of us now able to ride and willing to brave where our eldest led us.

Our enjoyment of such excursions did not last long though. Soon the rivalry between Minot and Boutage began to darken the whole affair. One would assert leadership over the other, and then of course the rest of us were forced to choose sides.

One day our alliances seemed to be set, made for the rest of our lives. We traveled to the Nook that day and rested by a spot by the lake, our favorite that was surrounded by yellow cliffs. Wild plants clung to the edges of a calm pond that our mehra’s drank from as Boutage and Minot left us behind to scout our perimeter. Nothing much happened by way of danger on these trips, but today we were surprised by the appearance of Mayak!

As Nanui drank, I brushed her and hummed to myself. Darlian was squatted over the water, cooling off, when I heard him gasp. I looked to where he was pointing across the river and up into the cliffs. Seleth was nearby, tending to his mehra, Treetop, and quickly ran over to Darlian to smack his pointing hand downward. He then turned his back to the spying figure Darlian had spotted.

“Don’t point! Don’t point!” He said.

Kuba then said in a hushed tone, “He didn’t see, Seleth. His back was turned.” Kuba immediately gathered his things and mounted his mehra, Jester, to find our brothers.

“Be quick, Kuba,” Seleth said.

“Okay,” he said, galloping off.

The Mayak warrior at the top of the cliff was holding a spear, and he peered down at us, his hand over his brow. We pretended not to notice him as Seleth suggested, to not act alarmed, but then another Mayak appeared. My heart raced with what might have been morbid curiosity, a mixture of both dread and excitement. The warriors spied on us then disappeared from the ledge.

We did not know what to do but Seleth acted with bravery, helped us gather nerves and prepare for whatever was beyond the ridge. It was not long before we heard the sounds of hooves approaching, a cacophony coming from two directions. Seleth, the only one of us armed with anything better than a worn and rusted dagger, stood his ground.

From the north entrance of the sandy bank the Mayak appeared, two of them fast approaching us. They were wild, faces scrawled with white paint.

Then behind us our brothers emerged from the south entrance wielding their scimitars. Seleth fell in with us as Boutage and Minot rode before us. It was a tense standoff with mehra’s circling, rising to their hind legs, and almost locking horns in challenge.

I trembled, thinking my brothers might die before my eyes, as I saw the strength of the Mayak warriors, their thick arms and deep cheekbones and hard set eyes. They were fully grown men and had the air of seasoned warriors. The leader wore several feathers in his straight hair. He looked at his comrade as if confused by my brothers’ behavior, as if a mistake had been made. He then said words to him and the two backed off, pulled the reins of their animals to show a they were not hostile.

This gesture seemed obvious to us—a truce. It seemed obvious to Minot too. The two Mayak pulled away, their backs turned momentarily as they then tried to swing around to achieve greater distance between my brothers. Only Boutage took this with either insult or as an opportunity to attack.

On the back of Onyx, Boutage lunged for them! Minot yelled at him, and so having been warned, the leader quickly turned and thwarted Boutage’s attack easily with an open palm, sending my brother to the ground! Minot then dismounted and ran for Boutage where the two fought, Boutage in a frantic rage trying to reengage the Mayak leader. Minot exchanged awful blows, and I could not stand it any longer, and so rode out alone on Nanui to them and shouted at them. I was between my brothers and the Mayak, who were laughing at us. Darlian and Kuba then came to me, shouting for me get away from the dangerous killer Mayak, who only sat in their saddles enjoying the scene of the eldest of the Khoorlrhani princes trying to kill one another.

Kuba jumped off White Mane and stood between them, and Minot pushed Boutage back hard and cursed at him.

“You are such an imbecile,” he growled.

Boutage, obviously embarrassed that we were protecting the Mayak from him, simply spat on the ground and dusted himself off. Seleth fell in behind Boutage.

“What do they want?” Seleth said coolly.

“Whose side are you on, Minot,” Boutage growled.

“Look at their face paint, you idiots. They are ambassadors! They wear Father’s cipher!” he yelled. Minot, wiping blood from his lip, then spoke with the leader and apologized. The leader then put his hands up, nodded and pointed to the white mark, a leaf painted on his arm band, a red dot in the center. There was indeed a story behind their presence in the Nook. The leader spoke to Minot, and as he did, I focused in on the language. I very much wanted to learn it.

As Boutage typically ignored all talks of peace, he did not know that these men traveled from the mountains bearing gifts for our father. He did not know that the mark they wore was to protect them should others, aside from the Khoorlrhani party sent from Arkya to meet them, find them first. Minot, who took all protocols seriously, knew most of this and was only surprised by their presence. Despite the embarrassment suffered by having to deal with Boutage, Kuba and Darlian and I respected Minot and saw his actions as more wise. This infuriated Boutage. I would pay later. I knew it.

The Mayak leader, Theseron, told Minot in his own tongue that they were a party of six. Three had been killed by tigers that attacked the cattle they brought as a gift. They were unable to find the Khoorlrhani party they were to meet, and so, when they picked up our trail, they naturally thought we were that party.

Theseron was shocked to learn we were the royal heirs, and he almost seemed to chide Minot for endangering us: mind boggling and stupid were words that I could translate from the dialect. Minot sighed as he nodded.

We agreed to protect and drive the cattle south with them as far as Kamina. We met the third member of the Mayak party who guarded the remaining cattle, at least sixty head. On the way Boutage glared at me, his deep dark eyes on me like a panther. Kuba and Darlian received this same treatment.

We left Theseron and his party at Kamina where they would rest and feed themselves and the cattle while in care of the warlord Tannis, who was expecting their arrival. Before we departed, it was expressed by Theseron that, since the Arkayan party was nowhere to be found, Minot should escort them the rest of the way to Arkaya the next day. Theseron did not feel welcome by Tannis and his men and worried treachery would befall him and his men. Minot agreed and sent Boutage, Kuba, Darlian, and me home, obviously the worst arrangement in my view.

Boutage reluctantly obliged Minot and we left immediately for Arkaya. The whole journey back, Boutage terrorized us. When Kuba tried to defend us, Boutage shouted at him, pulled his hair, and even pushed him off of his mehra, breaking his arm. Having made an example of him, Boutage then pointed at me, called me a “peace-making woman” and told me to stop my whining after slapping me. Poor Darlian was frozen stiff as we rode Nanui. We were a broken party, following the tyrant who purposefully led us the longest way home so that, under the dim light of the moons, he could abandon us halfway home. From that day nothing was ever the same between us, only vile competitiveness and abuse remaining.

When we arrived at the royal dihj, Darlian and I tiredly put our mehra in the stable. I then went into our home and, upon seeing my mother, ran for her. She embraced me. I buried my face in her neck.

“What is the matter?” Suwan asked. I could not answer for fear of more mistreatment from Boutage. I heard Minot yelling in the background, from the main section of the dihj. As it turned out, the party my father dispatched to the Mayak had arrived moments after we pushed off with Boutage. Minot and Seleth, relieved of his obligation to Theseron, took the short way back.

“Bullshit! It was not a seven hour journey!” Then there was another voice, Boutage, answering nonchalantly, barely audible.

“Then why is Kuba’s arm broken!? Why is Jeshoya running to mother! You want broken brothers to be king over! These are your games! Screw your goddamned circle of brothers concept! Before you came back, no one questioned my competence! If they were good riders, Kuba would have stayed on Jester’s back and he would have kept up!”

“Why do you hate everything and everyone?!”

“I do not hate them! I just do not paint the world with fluffy clouds like you do!”

“Right, just with dark clouds! You have no honor, breaking their spirits so! You do not serve them, just yourself?”

“I don’t answer to you! You are just a woman, Minot, a weak minded woman who keeps his brothers needlessly on the tit! When will you… WAKE UP…from your idealistic dreams of…”

Then we heard a tussle, the breaking of objects, the scattering of servants, and the overturning of furniture. We knew fists were flying. The we heard the voices of onlookers, shocked at such behavior. Aunt Nandee rushed into the parlor wielding a fighting staff of tied heavy bamboo. She struck mercilessly. “Get up! GET OUT!”

And this was the way our lives were then. I loved my brothers, even Boutage. There were days of sunshine, wild abandon, and camaraderie, and then there were days like this, dark, full of awful competitiveness.

Feeling dark inside the next day, I hid from the circle of boys again, sitting on the edge of my mother’s bed. She comforted me and listened as I lamented.

“I don’t much like being alive,” I said.

“Don’t say that, Jeshibian! Why would you say that?”

“Because everything is hard and no one loves. What’s the point of being alive if tigers eat you and your brothers beat you up?”

Suwan laughed, knowing me to be a dramatist. I did not hate life but was merely venting, frustrated by its terms.

She stroked my hair, and then asked, “What do you think the master would say to your tantrum here?” I shifted my eyes to one side, looking at the clay floor and its embedded green and yellow tiles.

I thought a moment and said, “Well, he’d say, ‘The point of love, young Khoorlrhani, is not to just have pleasure in your life but to learn how to love in spite of your displeasure!’” I threw in the few hand gestures that I knew the master would make. Suwan’s eyes lit up and she clasped her hands and erupted with a barely suppressed laugh at my impersonation. “Ah, yes! I think so.” Suwan sighed.

“You think he’d say that?” I wondered, and I smiled at my mother, challenging her to suppress her laughter, but she could not.

“Yes. I think it’s good that you can imitate him so well.”

“Why?”

“Because it means you’ve noticed how wise he is and you love him. I’m glad that I can see that in you.”

“No one treats the master the way Boutage does us.”

“You don’t think people have tried to mistreat him, eh?” Suwan said. Her eyes sparkled and narrowed. She seemed to hold onto a secret she was now willing to share with me.

“Who?” I asked.

“Your father, of course!” She laughed.

“Really?” I said sarcastically.

“So then I can assume by your tone you know this. Oh yes, worse than young Boutage really, but do you know how the master acted?”

“No.”

“The master acted with the bravery of the supreme warrior, Jeshoya, a bravery that no man in the land has yet to know.”

And in that moment I wanted to know what sort of bravery this was. My eyes were locked on my mother’s as I waited for her to elaborate.

“A bravery that held to the truth so much that Khoorlrhani-Tah could never lie to himself. Your father recognized that it was indeed the awful treatment given to Paen that Paen returned to him in the form of truth and that he had a lot to learn about love. And do you know what that said about the power of love despite our displeasure?”

I said nothing, only waited for the answer, thirsty for it.

“That it can change even the darkest hearts, though it may take years, decades, lifetimes. It changes that heart to want to give love more than receive it. It changes you, son, if you choose that over your comfort. No sword or armor will ever compare to this, my darling. It is unbeatable. So think on that the next time you want to throw a tantrum about the discomfort of life.”

I smiled. My mother gazed at me and caressed my cheek with her finger. She then pointed to the entrance of her room, instructing me to leave.

“So do not hide in here with me, Jeshoya. Be in the world, your world of rotten brothers, stinky mehras, dust, bug bites, swords and armor, and learn to love it despite the displeasure. Listen to the master and do as he has already shown you, my sweet one. Okay?”

“Okay,” I said, then ran out of her room.

That particular night, I knew the master was back from his travels and would be in my father’s council chambers. So I ran down the dark lower passageway—slipping in between the shadows untouched by the evenly placed torches that hung on the vine covered wall—that led to the lower depths of our dihj. Along the way I danced.

Restored to my humor, I wondered happily if my heart could change in the way Suwan told me it should. What was the supreme warrior? What kind of bravery could withstand all disappointment in life that did not require a thirst for brutality and acts of conquest and retaliation? Was it real? I wanted to know. I hoped for it, prayed for it. I would go straight back to the circle of boys if I could become that. I danced to a rhythm in my heart that led me to the master! I traced my finger along the complex patterns of the tapestries that hung on the cold grey stones of the walls below.

I could hear the voices of Master Paen, Minot, my father, and the two Mayak we met days earlier. In the hallway, I sat with my back against the wall beneath a torch by the curtain that hung over the entrance. I gazed upward at two massive stone statues opposite me and right before the curtained entryway, sculptures of massive tigers baring their teeth, their large granite eyeballs glaring at me. It was a twin representation of Tiaga, the tiger goddess. I gawked at them for some time, and then I peaked beneath the tapestry to get a look inside court.

“Come in, Jeshoya,” I heard the master call. I was never good at concealing myself. I parted the curtain and entered. There was laughter as I did.

“If you were not so loud in your dancing, you might have stayed hidden, but why hide such joy?!” the master said, grinning. My father glanced at me and smiled. He seemed to be enjoying the same rhythmic tune playing in my heart, which was spurned by my thirst to be in Paen’s company, delightful thirst. I swayed back and forth, happily.

I came inside as was commanded by Paen, and I was met by the pressing eyes of onlooking strangers. The two Mayak warriors my brother and I encountered were standing before Khoorlrhani-Tah. Two others were among them who I had not seen before. They all grinned at me as I sheepishly entered, pushing past the spear wielding Bakuwella guards and into the clouds of incense within the interior. All of the lords were present, all seated, and all dressed formally in brocade kaftans and backed by their standards and the fourteen men in each entourage. The entirety of the Khoorlrhani nation was represented in a grand multicolored crescent of seated bodies before my father and the four Mayak.

Paen stood near my father. Minot stood by the leader of the Mayak, and between them and my father was gold spilling out of metal cases and onto the beige tiles, a measure I had never seen in all my life! One could say it was a significant amount of all Mayak wealth. There was a chuckle at my wide-eyed beholding of it.

“My son the dancer,” my father teased, introducing me to the hall. Everyone laughed. Minot translated what my father had just said to the other Mayak. Their eyes narrowed because of their wild smiles. They stood, elegant figures, pure, wild, ringed ears, straight braided hair, necklaces of animal teeth, and skirts of leather.

I shrank in embarrassment, but Khoorlrhani-Tah beckoned me, his many ruby-ringed fingers curling gently against his wide palms as a gesture for me to come in and take a seat on a vacant cushion by his side. He was warm to me. I went to him.

The Mayak leader, Theseron, resumed speaking to the tah, glancing at me and laughing as Minot translated.

“Enksosi, your youngest son, has a very good heart. I would be proud to call him my own,” Minot translated, and then he winked at me.

Through these four men, two of which Boutage nearly cut down, Unat the tah of the Mayak had sent his regards to both my father and Paen. Peace was being made. I was overcome by happiness and noted how Paen seemed to glow that evening.

“He agrees,” the Mayak reaffirmed. “Twelve families of Mayak and twelve of Khoorlrhani and a mixed force to keep the order for five years, this is acceptable. Unat Mayak-Tah agrees to this and the rules presented to govern the town.”

The cattle the Mayak brought were an offering, repayment for the many years of raids on Ketique ranchers in the east. The gold, many trunks of it presented before my father that night, was repayment for damage done to fields. My father was overcome by this gesture. By Paen’s work, by his travels to convince Unat, the Mayak were now ready to end the old conflict.

The Nook, our former playground, was now to be mutually shared territory. For centuries our tribes fought to control this region. Both tah’s agreed now that an equal number of families would settle there. If the peace lasted, then the Khoorlrhani would consider intermingling further south, opening their borders in years to come. It was a radical plan, again one that Paen was behind, for as the terms of the agreement were discussed in this final moment, my father struggled.

It was the warlords gave him pause. They looked on disapprovingly.

“I understand that this is difficult, but the idea of Mayak and Khoorlrhani coexisting must come to this event. It is you who must bridge the divide. Time will not do it for you,” Master Paen said, his hands turned upward.“How else could it happen except by agreeing to intermingle, share what is given on the One Great Land. And it must be done right now because there will never be a more convenient time, and you cannot wait until the noble lords become agreeable to this plan. Mayak and Khoorlrhani must eventually become something different, undivided. So what is that? How do we approach it? I can show you!” Paen said, Minot translating to the Mayak.

He then walked further out into the room, addressing everyone. “Great men destroy the confines of tradition by believing more in the truth and less in this cheapened standard of their sword that we live by. These…destroyers are truly great tahs! You see the metaphor of the sword is of truth, temperance, community, cooperation, not of revenge, of obstinate politicization, not of mere conquest as you’ve mistaken it for. Vulnerability is what fuels true living. Vulnerability! It can be done, but only if we cut through these political obstructions we have created among ourselves.” Minot translated as Paen glanced at the section of the room where the lords sat, their arms folded, their heads shaking in stubborn doubt.

My father sighed and said, “But there has been so much Khoorlrhani blood spilled in the Nook…”

“Yes, brother, let us now forgive the debt of an eye, a tooth, a leg, a life. All of it forgiven and agree to start again. You worry, ‘How will the lords react when told we must change? What will they withhold from Arkaya? How will they align themselves against me?’ Your mind searches for an answer in the darkness of the future. I say that it does not matter what these chiefs think if you are entirely aligned to me. If you are aligned to me, that future does not exist and so there is nothing to fear.”

And there was a laugh from among the crowd, a deep sinister chuckle. Paen’s words were seen as a direct challenge by the lower chiefs, mayors, and wealthy citizens from the outlying towns, who scoffed in their protest. They wanted to continue to profit from the war machine. Their agitated sounds began to resonate within the court. Lord Dajaai of Ketique rose and turned to look into the crowd with a stern face, silencing them all.

“Boutage-Tah, do you doubt me? Do you doubt that I could withstand their reaction against the policy of truth? Have I not already demonstrated strength, love, and utter reliance upon the truth? I ask you as well Chiefs Tannis, Shakuba, Chobaza, Bombazu, and Dajaai.”

Dajaai came forward on his knees, bowed to my father, and said, “I will follow you and Paen, enkosi. His words are sane.”

“Coward!” another faceless voice shouted, and Dajaai rose again, hand on the hilt of his sword at his waist, challenging his accuser with sharpened eyes staring through an orange band of ceremonial paint across his eyes. He wore a slender mid-thigh length black kaftan, gold patterns across his shoulders and a striking set of golden eagle wings displayed across his chest. His mane of hair was decorated with dyed feathers, gathered and tied neatly in three sections by golden bands into a singular braid. The room was silent as Dajaai again, by right, sought out his accuser, walking the smooth tiles of the front row on golden sandals. My father patiently awaited the outcome. No one dared challenge Dajaai. When every pair of eyes was looked into by the Lord of Ketique, they averted. It was then settled. Satisfied, Dajaai again seated himself.

On their knees, Chobaza and Bombazu both came forward, bowed, said in turn, “I will follow you and Paen, enkosi.”

My father’s nostrils flared as he leaned forward, his eyes narrowing upon the master, a smile coming to his lips.

“You are right, Master Paen. This will be done. I have been wrong. I do not doubt you. It shall be done.”

Then there was more shouting, a roar of it as Bakuwella pressed more deeply into the room and as Minot screamed the translation of my father’s words to the Mayak, who then smiled, shocked. They then, all four of them, stretched themselves onto the floor!

My father was again overcome, not believing his eyes, and he was so inspired he removed his crown, stepped from his bench, and gathered the Mayak leader up, embraced him, and kissed his cheeks.

I watched the northern lords, Tannis and Shokuba rise, twenty-eight men behind them, and bowed. The lords and their retinue walked out the court entrance in protest.

Later that festive night there was laughter throughout the dihj. The servants were kept up late preparing food and playing music. Our cavernous parlors were full, the stoves roaring and glowing with warmth, the Mayak ambassadors entertained and made drunk. The entire family was assembled, uncles and aunts and cousins and grandparents, all telling stories about our meeting Master Paen. For the first time ever, I saw my father holding my mother close to him. She beamed as she looked into his eyes, as if the man she fell in love with had finally returned.

The rains began that day, a torrential downpour of the monsoon season, marking a period that seemed to clear the way for a new time—a prolonged peace. The main family room, a large torch-lit area over which an ornate wooden frame held up the vine roof, was loud with the sound of the downpour. There were several tables covered with fruit brought in that would have otherwise spoiled in the warm rain. The floor was smooth clay tiles, and my younger cousins slid across it in their play. I snatched a banana from the table, chased my cousins for a short spell, and then joined my brothers and parents in one of the smaller parlors tucked behind the family room.

They were talking openly and with humor. Their respective ghosts somehow had disappeared, outshined by the glow of the master who was in the center of the room. The conversation shifted to the future, and Master Paen again reassured my father that to worry about civil war was useless.

“The chiefs being stirred up is inevitable even without talk of peace to aggravate them. The Khoorlrhani nation has gotten too big. Your empire will inevitably divide as the continuity of ideas take on different shades along different lines. All can divide peacefully or not—it scarcely matters. This is not about the outcome of your empire; it is about your enlightenment, your freedom. The peace that matters is that peace, the peace that I am.”

As I looked at my father, I realized that Khoorlrhani-Tah had left his crown on his jade and ivory bench. He had forgotten it, distracted by Paen’s work, distracted in regarding the Mayak, who had bowed to him that evening as brothers. For that evening my father was free, happy as if Paen had removed an obstruction without my father knowing. Just as I made that observation, Paen glanced at me and winked at me.

And we were quiet. I swayed, loving Paen as he radiated and everyone just looking at him in silence. He was perfect, so unlike my father or me.

“If Lords Tannis and Shakuba plot against you, so be it. If they ride upon Arkaya, we will defend ourselves. There is no point worrying about what they think.”

But I knew my father would again worry, I could feel his pattern coincident with my own, my need for a crown of sorts. He would again become self conscious and seek his crown out. I knew this just as I began to know myself to be the same. In viewing my father, I saw my own reflection.

I did not worry about a fence being torn down, but rather, that I would not have one. Though on the surface I wanted to know what the supreme warrior was, how that concept could be real, how it could change me, I secretly conspired to exploit it, to make a life that was painless and to serve to create my own fence of invincibility. Paen knew, and with a wink, reflected this back to me.

I indeed fantasized about being the supreme warrior, full of vigor and grace, never wrong, never in need, as I played in the forests and in the cavernous underbelly of our royal dihj. This of course was the shadow of Jandee as I dreamt who I would become.

Chapter 8: The Threat of Mandee

One day, nearing the end of my ninth year, I was playing by the streams with my sisters. I had found the most vibrantly colored butterfly, its wings a beautiful pattern of oranges, turquoise, and dark blue. It let me get close enough to see it but never close enough to capture it satisfactorily with my eyes. From behind me, I heard my sisters splashing each other in the water. Suwan moved from her sunning rock and into the depths of the pond. I watched her for a moment as she untied her hair and moved waist deep into the water. Her skin richly deep brown, as she waded she ringed her wet hair then spread it over her shoulders. She saw me from below and waved at me. I smiled then resumed my pursuit.

The butterfly doubled back and I chased it down a small hill. I was intent on studying it. It flitted to a deeply shady and moist spot beyond some shrubbery. As I circled around it to catch a glimpse, I stumbled on a rock and fell, and then I heard the rock overturn.

Something, an animal, snapped twigs and ran away. I heard it making a commotion along a path downhill but could not really see it as if it moved beneath the leaves. I brushed myself off and then saw my winged friend a few feet from me. It flew again, further downhill, and I gave chase. Finally, it alighted on a rock by the creek.

Beyond the small boulder I could see Anya washing her feet, and my mother was approaching her. I focused on the butterfly, my two hands ready to catch it when I pounced. I jumped and missed, but then something was aroused. It hissed!

I fell onto my back and it was right before me, a large asp, its crimson hood majestically flared. I could not move. It stared at me. From the corner of my right eye I saw another one near Anya. Her back was turned to it. She turned and it struck her!

I tried to scream but only managed a gasp, compelled to be silent by the one before me. Be still or die, it seemed to say ever so clearly.

Anya was struck again, and she then screamed and cried. She stomped and was struck again. My mother ran toward her.

“Anya!” Suwan screamed. “Nandee!” She scooped up Anya only to be struck by the snake. It did not slither off but circled, slithered over the water and then struck my mother again. My mother screamed. The world seemed to shatter.

I was paralyzed with fear. I could not bear to look at what was actually happening. I stared into the eyes of the snake that promised to kill me should I move.

You are Jandee, I thought, in my panic.

It answered with a hiss. She did not like being named. My Aunt could be heard running toward me. I heard her halt in her horror as she saw me pinned below.

“Oh! Jeshoya, don’t move,” Nandee whispered. I did not move, every fiber of my being working against the reflex to flee.

“Stay there. Do not flinch,” Nandee warned.

You are Jandee. Leave us alone, I thought again, terrified but willing to receive her sting as an answer as there was no escape.

The snake hissed again, wavered, retracted her hood, and then followed her sister Mandee into the bushes. My aunt rushed to me and grabbed my hand. The servants rushed my sister indoors, and Nandee accompanied my mother and me.

“Khoorlrhani-Tah!” servants shouted. They rushed to get him.

We placed my sister and my mother on beds, desperately cleaned the wounds and tied off their limbs. The servants cut out and pressed out the poison, sucked it out, used herbs, prayed, screamed and howled, but my sister died within one hour. Nandee and the other aunts and cousins, lamenting, carried her body away.

My mother lay in bed. She suffered and cried from losing her daughter. I held her hand throughout the night. She looked at me in the dim glow of candlelight, her breathing labored, but she gripped my hand. Her mouth grew dry, her eyes red. As the sun began to rise for morning, she said my name.

“Jeshibian… I must go now…”

“Please don’t go, Mother. Please. Please,” I pleaded, feeling helpless. “Where is the master?” I asked looking around me. No one could answer. He was away. “Please don’t go, Mother.” I prayed, “Please, oh Ashuta, please.”

I stayed close to her. My father sat next to me. As my grip tightened on Suwan’s hand, hers lessened on mine.

“Mother!” I cried, shaking her hand.

She no longer gripped back. My father took me toward him, held me, a forearm against my chest,

“You must accept it, Jeshoya,” Khoorlrhani-Tah lamented.

“No.”

“You must.”

“Please,” I pleaded for the last time, and I then I died inside.

After the ceremonial three days, we cremated Suwan and Anya’s bodies. I can now look upon that day in hindsight as bittersweet as it began with my whimsical chase for the colorful hues and tones of life and ended with the blackness of my sister’s and my mother’s death.

I was learning that comfort is fleeting in this real world full of just as much tragedy as victory. I could not understand that happiness itself was independent of these events. Instead, like my father, I reached my hands into the rose bushes of my self-entitlement and was pricked by the thorns of my resentment.

I thought, Ashuta, why? Why did you betray me? Why did you take my beloved mother and my sister so cruelly? I was angry, so angry. Why did you make me so helpless that I could do nothing but be still and accept my mother’s fate!?

Had I not heard the master’s story of the first brothers, of how they each demanded Ashuta’s grace rather than accept what was given? Did I forget what my mother had told me about the supreme warrior?

Indeed I did, for I sat in my father’s throne room heartbroken. I could not hold to the wisdom the master had given me. Somehow, it was not relevant to me, to the very moment of my life as I lived for the past. I avoided Master Paen, angry with him. Why was he not there to save my mother and sister!? I shouted these questions inwardly, made these complaints in my heart. I wandered the jungles alone, and then one day, when I thought I was alone, I screamed at the mountains, “Why did they have to die?!”

A voice called over my shoulder, “Because it was their time, Jeshibian.”

It was Minot. He had been tracking me. I tried to run past him, but he snagged me with his long arms. I writhed, kicked, screamed, “Leave me alone!” But I could not get free. Minot held me until I finally relaxed.

“Now sit!” he said. I obeyed. “Wipe those tears, Jeshibian.” I obeyed.

We were quiet for a while. He then said, “Do you think you are the only child our mother left behind, the only brother Anya left behind?”

I had not thought of that.

“Everyone in the palace, everyone loved them, and was loved by them.”

“Sorry.” I sobbed. “I’m sorry.”

“I understand you are confused, but do you see now how you think, that you’re so special, and how you forget the rest of us here with you?”

“Sorry.”

“Do you see how that makes me feel, makes Boutage feel, Kuba, Seleth?”

“I know,” I whined.

“This is life,” Minot declared, and it angered me.

“I don’t like it.” And there it was, my rejection of life as it was because I was clamoring for an idea, a past love, as the master said I would.

“This is life!” Minot said.

“I don’t like it!” I screamed in contempt. And then he shook me, his large hands on my shoulders.

“This is life!” he yelled at me, not accepting my unreasonableness. I calmed down. “This is life, brother. You cannot change it,” he said, and let me calm even more before saying, “What is your duty in life? Do you remember, or have you so easily thrown out what the master has taught you and decided instead to be a spoiled brat. Use what he gave you. What is your duty? Tell me right now or I’ll be so mad at you, Jeshibian Khoorlrhani that…”

“To manage love,” I said. I could not bear Minot being mad at me.

“Even when…?” Minot pressed.

“To manage love even when it seems impossible.”

“ So, have you spoken to Master Paen since? Have you expressed your grief in knowing his devotee was taken away from him?”

“No.” I broke into tears, now seeing the cruelty of my privacy. “I’m sorry,” I said.

“You might want to tell him that. You are not the only one hurt by this, brother. We are all survivors and all obligated to help one another heal.”

“Okay,” I said as I squirmed and sniffed.

“Let’s go home,” Minot suggested. I saw that day why I loved my brother. I knew that day what it was Paen I loved in Minot as well, for in this moment Minot, who was dealt this blow we both endured and still managed to straighten me out and stand with so much grace, showed me so much strength. Out of all of my brothers, indeed Minot stood out, shone, and did not hide in his grief. Instead, he came to us all.

With him near, the thorn was removed from my heart and I knew from that moment on, as he looked at me sternly, that Minot expected to see me standing more strongly on my feet from now on. I hadn’t the clarity to see it then, but my mother’s death made way for my seeing Minot in this totally different light. Though frustrated, and seeming to be confused at times, Minot was Paen’s devotee. Paen looked on him with the same sternness as Minot was now looking on me.

I could no longer run now, and Minot would no longer console me. Instead he reminded me of what our master taught, to see the bigger picture, to love. To love as the mosquito draws blood, the wasp breaks the skin, the snake bites, only to love. To love while the tiger hunts, the brother betrays, and the mother dies, only to love. To love while all else fails, but never to fail at remembering and holding to love for, as the master had taught me, to fail at loving was truly to fail at noticing who I really was.

Minot n pushed me past my grief and took loving care of me, fed me the strength he stood with. We rode together much of that summer, mostly alone but often times with Darlian whose heart was also torn by our mother and sister’s departure.

Minot did well to keep us together, the three of us, to focus us, to let Suwan and Anya go, and to heal.

Discussion ¬