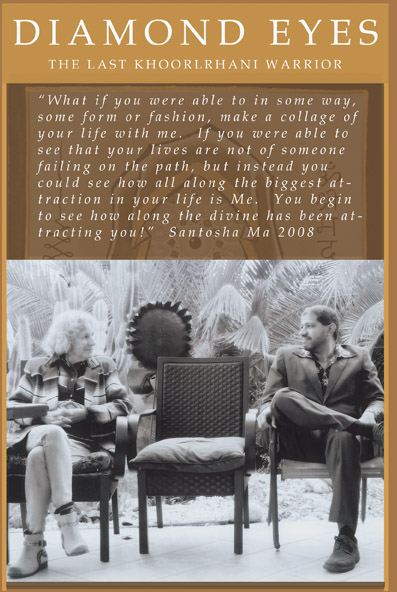

Dharmic Sci-Fi Fantasy: The Last Khoorlrhani Warrior – Chapter 1-2

Dharmic Sci-Fi Fantasy: The Last Khoorlrhani Warrior

The Last Khoorlrhani Warrior, is the second in the series of novels written for the Diamond Eyes series. It centers on the next generation of Khoorhani, whom Paen of Eastern Genia serves in his role as the Master. I’ve posted the first nine chapters out of about thirty three. Use the menu below to read the first nine chapters, or scroll to the bottom to download a copy. Enjoy

The Last Khoorlrhani Warrior, is the second in the series of novels written for the Diamond Eyes series. It centers on the next generation of Khoorhani, whom Paen of Eastern Genia serves in his role as the Master. I’ve posted the first nine chapters out of about thirty three. Use the menu below to read the first nine chapters, or scroll to the bottom to download a copy. Enjoy

Part I – The Great One Land

Chapter 1: I Am Jeshibian…

3rd Dynasty Arkaya, the era of the master’s return (4191 B.I.)

My brothers call me Jeshoya. In my people’s language, Jeshibian means sunlight or sunshine. Jeshoya in Khoorlrhani, pronounced Kor ronee, translates to ray of light. As I write this, I am twenty-nine years old and have been to places never imagined by my tribe. We were once the Khoorlrhani and we lived in the southern regions of the Great One Land known as Genia. I grew up with many brothers and two sisters.

What line do I trace to begin to tell you who I am? Of course the quill must dip itself well within the inks of the past. So then…

My father was once the king, or tah, of all Khoorlrhani, and he sat upon his throne in the great city of Arkaya. This of course made me a prince, a potential successor to his crown, inheritor of his kingdom. The benefit of hindsight allows me to appreciate the events that unfolded in my life and to thank Ashuta that this was never to be.

I’ve learned many languages since my travels, and I have discovered that many people find it difficult to learn Khoorlrhani words. As a young prince, I spent most of my life in Arkaya, never assuming that one day I would leave, compelled by an attraction greater than any promise of worldly wealth; but neither do I want to give away too much too soon nor linger on this element of my tale.

To describe myself, I would say that I am of average height for Khoorlrhani man my age, which is about six feet tall. My ears, like all those of the Great One Land, can be described as pointed, sharp at the ends, or elfin, a distinction that only bears relevance in light of the events of this story, its further unfolding, the scope widening to tell more about my travels.

I have my father’s face, as I’ve been told by my relatives, light brown skin, deep-set eyes, wide cheek bones, and a thick mouth. My hair is light brown, coarse, and twisted into dreadlocks, the traditional fashion of my people. When I was a boy, the tips of my matted locks were dipped in a strong green dye to signify my being made a Khoorlrhani warrior. It was my older brother Minot who initiated me. I will tell you more about him in time.

The elders, the aunts and uncles who knew those before my time, said I resembled Kalid, the sage of a generation ago who died at the Great River. There were many stories about Kalid passed down by word of mouth.

He was described as having deep-set hazel eyes, which the relatives mainly focused on when making their comparisons, though my eyes are actually more green, an uncommon trait among the Khoorlrhani but rather typical of Mayak, our sworn enemies in the north.

By nature, I was a worrisome soul, always thirsty for validating and comforting answers, something to make sense of the cloud cover of the life I was living at the time. Family and friends often wondered what it was I was searching for, as if all answers seemed obvious to them. What was it I searched for? I didn’t know myself, but what was before me, my life in Genia that was before my very eyes, could not be it.

My story, or rather our story, the everyone story, I have ached to tell for some time; but as I have always been distracted, I have taken a long time to gather in a concise enough image, all its threads woven well enough, that I could stand behind that image with confidence.

In actuality this is a story of attraction, attraction over and against self and world masked as a journey of rebirth stemming from the great and awful forgetting and then being handed over to that which reels into focus to the sharpened eyes of the famished soul yearning to witness it; that which smashes our ideas into glorious bits to reveal our sameness, undeniable. That is what I wish to tell you about, if I can manage.

For now, I will begin my story simply, with where I began my quest, in my home where I, my mother, my father the tah, my brothers, and the great Master Paen, pronounced Pi Yen, lived in the city of Arkaya.

Of all the lands in the great one-land-of-all-people, and of all the cities that my father’s rule extended to, no portion was greener than Arkaya. She was a thick humid land with rivers running through her, white-topped mountains in the distance disappearing into thick and stormy cloud cover and backed by rich blue skies full with radiant yellow sun.

From where we played as boys in the deep jungles, through tall trees and among the big leaved taros and vibrant orchids, we could see the high forms of stone towers climbing above thick and endless fog and greenness; and all around us were thick waxy leaves, vines, deep reddish mud, dragonflies, and at a great distance, the giant fence that protected the capital city from our enemies, the Mayak.

The Khoorlrhani flourished in the jungle lands of the Genian Valley. As Paen told me, our people were once hunters and gatherers, the Great One Tribe, tens of centuries ago, but during the period leading up to my lifetime and the lifetimes of my brothers, ours was the largest kingdom in history and a great nation-state known across all the land. Arkaya was the capital city surrounded by six prefecture cities run by chiefs, over whom my father ruled as tah—king, emperor, overlord, supreme warlord, God.

The Khoorlrhani, like those of other lands, the plainsmen in the east, Cwa and Bantu in the south, and the Mayak of the north, were generally brown skinned, separated by those others only by subtle degrees of hue.

The only Khoorlrhani who were distinguished easily by their complexion were those from the southern most regions near Kushite. They were very dark skinned.

It was typical for Khoorlrhani to wear their coarse hair in coiled and bound locks or braids, or for some to completely shave their hair. The men wore their hair long and pierced their noses, while young women wore their hair short, often in small knots, until they were married, and they also decorated their skin with tattooing or beadwork.

Women wore imported silks and other fine cloths of vibrant color. The men typically wore simple long skirts and sandals. In the northern towns, towns of higher elevation where the air was cooler, Khoorlrhani wore skins and fur boots during the winters. The women often wore tunics or kaftans, and those from the outer towns just outside of Arkaya often went shirtless like the men. From the homes of our dwellings that we call dihj one could smell rich spices intermingling with other pleasant and unpleasant aromas of daily life.

Arkaya, being the hub of commerce in central Genia, produced a vastly intermingled culture, influences extending from as far as the Bantu and Cwa territories—from which many traveled to pay tribute to our father and trade their goods in Arkayan marketplaces—to Eastern Genia where plainsmen were known to speak of our tah.

Chapter 2: Warriors and Warlords

“We are not a true tribe, nor are we original!” Master Paen said to me. He was correcting me when I was a small boy and proudly referred to us as the original tribe of man.

I was stunned as he turned over my idealistic assumptions for the very first time.

“No we have become the awful persistent machine. We are something else now, tribal only in a historical sense but no longer the great circle of cooperation we once were. There is no longer nobility in the word Khoorlrhani in my opinion,” he said flatly, bursting my pride, my naïve prince’s sense of self-importance.

The tah of the Khoorlrhani was regarded as God. This went back to the times of antiquity, before there were cities governed by lower chiefs. So, naturally, my father’s godliness meant I was the son of God, right? This was the assumption that the master addressed in his correcting me.

Master Paen told me that, in the earliest of times, the tah was indeed God, but now the tah was only a wrathful figurehead of red face paint and eagle feathers, a simple historical habit. To me that meant I was to inherit the lack of wisdom that was my father’s lot. This disturbed me as a young boy, but Master Paen never allowed me to linger in such thoughts.

Paen explained to me that where the tahs went wrong was their fall into greed, selfishness, and the hording of Ashuta’s gifts. The resources of the Great One Land were parceled out in return for loyalty to a tah, who became an “unenlightened fool,” as Paen put it. “Instead of serving as the example of abiding in the natural ebb and flow of the already-happy-here in the Great One Land.”

The mistake occurred far back in history, but since then, the reign of the tah was simply handed down from father to first born son as it was assumed that the blood of the royal family was holy.

“The tahs have forgotten humility and are no longer benign in nature, and so the people have learned unnecessary ambition,” Master Paen lectured me.

My father’s kingdom was larger than what one man could reasonably maintain order over, and so it was subdivided. The cities, their heraldic standards, and their respective chiefs or lords were as follows:

|

Kamina in the north, a city above the great lakes, beyond which we have driven away the predator manju tigers. This city is ruled by Chief Tannis the Bold. |

| Tanaga in the west, where our armies have pushed the Mayak across the rivers. This city is ruled by Chief Shakuba the Loyal. |

| Kushite in the south, where the Bantu and Cwa peoples trade and pay tribute to my father. This city of stone towers and pyramids is ruled by Chief Chobaza the Graceful. |

| Isiwa in the east, where Chief Bombanzu the Observant keeps watch in the distance for that which may come over the Genian Highlands. |

| Ketique in the far east where the great Master Paen first appeared to us. This city is ruled by Chief Dajaai the Reasonable. |

| And in Arkaya the capital city my father, Boutage the Power Mad to most, sat on his throne, and Toumak my uncle served as general of his large army. |

Each of these chiefs was given land and each of these lords had vassals in their service, captains who ran subdivisions of their armies and were also given land and granted an audience with the tah.

“How do you give the land?” Paen, who once wandered the plains in the east before coming to us, would ask my father.

“By my decree,” my father would answer, tight lipped and obstinate.

“When was it ever yours to give?” Paen quipped.

Our warriors could be seen throughout Arkaya riding on black mehras, pronounced May Ra, our great horned riding beasts. They also patrolled into the jungle along the perimeter of the great fence and beyond and mingled among the inhabitants of the Arkayan merchant towns.

They filled the taverns, their tables cluttered with silver-studded black leather gauntlets and blackened steel helmets, their raunchy demeanor permeating the atmosphere. They stood guard along dirt roads near the marketplaces, and they patrolled the wheat and corn fields that spanned a great distance in our lush valley.

Of Arkaya, the master said that it was our nation’s obligation to, in our having much, serve with generosity and instill a greater sense of community rather than skillfully holding defensive lines as we did.

“But it does not matter really. It will all fade. All things die off,” Paen said.

The Mayak, our enemy, their standard the sun and their true numbers unknown as they were scattered all along the entirety of the Genian Highlands, were ruled by Unat the Cruel.

It was said that five of our Khoorlrhani warriors were only as good as one Mayak. It was said that the Mayak’s harsh life in the cold mountain tops made them fierce—and it was Khoorlrhani wealth that made us soft.

“Propaganda!” Master Paen would say with a chuckle. “They bleed like any other men. This is just a time of rattling sabers and living up to some silly idea of what brave men must do. All this fighting-of-roosters is meaningless.

“The Khoorlrhani nation is only an idea, Jeshibian. Put these silly ideas away and put your attention on what I have to show you!”

During my adolescence the master would say these things to me to snap me out of the patriotic trance I slipped into from time to time. As a boy I fantasized that I would serve my father’s army bravely and without question, and I assumed admiration, respect, manhood, land, a woman at my side, and ultimately a sense of greatness, would follow. The master did well to show me the absurdness of my ideas, as what he had to show me went deeper than the mating game politics of Khoorlrhani warfare, as he once coined it.

The ranks of my father’s army grew with young men who knew that they were made of the right stuff. In their minds, they could withstand the ferocity of the Mayak! My brothers wished to be among those men, but they thought themselves better for they were sons of God; and as children they play acted, fantasizing about fulfilling their sought after destinies as tah, as God.

Admittedly, as the master’s criticism of my attitude pointed out, I also wanted to be one of those men. He told me though, with a grin and a wink of the eye, to love being myself “as is.” And I accepted this, loving him and trusting him entirely. However, since I was such a doubting soul, I did not listen deeply enough for I was still certain there would be a moment where doing what brave men did would cure me of my doubtfulness and quench my thirst to go somewhere else, to be informed by means of adventure that I was great.

“And that is how you and the other Khoorlrhani are all self absorbed and unoriginal,” the master teased me.

My brothers were hungry for martial duty, hungry to meet that call to adventure, and I felt I was hungry for it as well. After all, I was Khoorlrhani, wasn’t I?

To become a Khoorlrhani warrior with broad scimitar, black horned mehra, a head of dyed dreadlocks to denote acceptance into the corps, to defend the nation for the honor of the tah was what most young boys longed for.

A warrior did what his captain ordered him to do. He was strong. The women loved him. He had blind faith, as did the captain, all subordinate along the chain of command to the top, my father the ultimate authority.

A warrior wore feathers along the right side of his helmet or banded to his right arm. A warrior in my father’s army was branded with the symbol of their prefect: circular bolts of lightning or the claw of the manju tiger. A warrior beat his chest with the flat side of his curved blade upon seeing a superior officer. A Khoorlrhani warrior ate a bowl of fear for dinner so that he was inclined to the flavor of it on the battlefield. A Khoorlrhani warrior killed Mayak. That was his greatest aspiration. The women loved him, the tah needed him, the common man respected him. The warrior was fulfilled by this recognition.

“It is worse than tribalism, the awful spawn of it. The outcome is only more darkness in an already dark world,” Master Paen said.

“You see, Jeshibian, we are fast losing the direct link with the land because we cut her up and sell her like she were a mehra,” he told me.

“Look around you! The majority have broken wills. They are slaves to the minority who only work in abstract dealings. All the while the commoner hopes, works to attain land and self-importance, and you at the top develop alliances based on your right to keep what you have, to save political face, and to fly these stupid flags of division. It is silly. It will not work in the long run. Only love works and is the basis for true culture,” said the master to each of my brothers.

But we did not listen for we all felt entitled to our comfortable destinies, princes who would be kings. It was the burgeoning engine within our hearts, this inclination toward Khoorlrhani power.

“Or,” the master said, “this dark inward momentum will become something else, something more horrific, and more degraded. You will see.”

I admired the Khoorlrhani warrior. In my childish mind, the Khoorlrhani warrior seemed a fascinating and diverse fighting machine. There were many denominations of warriors, from mercenary to royal guard, from hired hood-assassin to centurion. The art of combat was popularly practiced among men and boys, but warriors of rank were only from noble families, such as mine, or those of my father’s chiefs. There were masters of the fighting arts who practiced with the adepts from the time of antiquity, those who studied the deadliest animals in the jungles and imitated them. These masters were in service to my father—even Master Paen but not the in the way I assumed. My brothers and I assumed we were the entitled sovereign inheritors of divinity.

My brothers obsessed about attaining fighting form, the form of the tiger, the form of the ape, the form of the asp, and they meditated on learning the full range of weapons: the spear, the bow, the staff, and the many different styles of swords made by the blacksmiths in my father’s employ.

My brothers were fierce. As a young boy, I both feared and admired them. I was the youngest and so mimicked them, and I was raised on the idea that our destinies were the same.

The deadliest men of the Khoorlrhani territory belonged to my father, and they made his army what it was, a force to be reckoned with. He kept his chiefs, his warlords, loyal by preserving their sovereignty, their right to their given land; but he made it clear that what was given could be taken away by his war machine of millions.

A circle of the most dangerous men surrounded my father. They were called the Bakuwella, hooded protectors of a sect dating back to an ancient time when the Mayak learned painful lessons to be more protective of their tah.

There are stories of chiefs who crossed my great grandfather, a hard man who ruled with a crown of fire affixed to his head that held within it a strong and ruthless mind. The stories told of how servants found their lords poisoned or beheaded. My father was very much like him in both temperament and his ready use of force.

He was reputed to be a dangerous man, and he was hated by the many who felt the sting of his Bakuwella. To those hungry for glory, my father was seen as a great and powerful tah. To serve him, to spit blood while entranced and whirling in the sacred drum circles and to be dispatched to the north to fight Mayak, was an honor to many.

We are Khoorlrhani. Nothing will stop us, and nothing will dare try, they chanted.

But still, with so much perfection of the martial arts, with so much brawn and dedication to service to the tah, confidence in the Khoorlrhani notion of infallibility was splintered. That splinter was the master for none of my father’s personal assassins or centurions could compare to the grace and form of Master Paen.

Whether singularly or amassed against him, they failed. It was already proven years before my birth, but that is a tale already told in volume one of The master Returns.

“The Khoorlrhani nation will be cut up by its own swords and ruled by its own men-at-arms soon enough, and then where will your father be? He’s lost, feverish. He either cannot see it coming or ignores it—like he ignored me.”

One man, my master, could defeat them all!

Discussion ¬